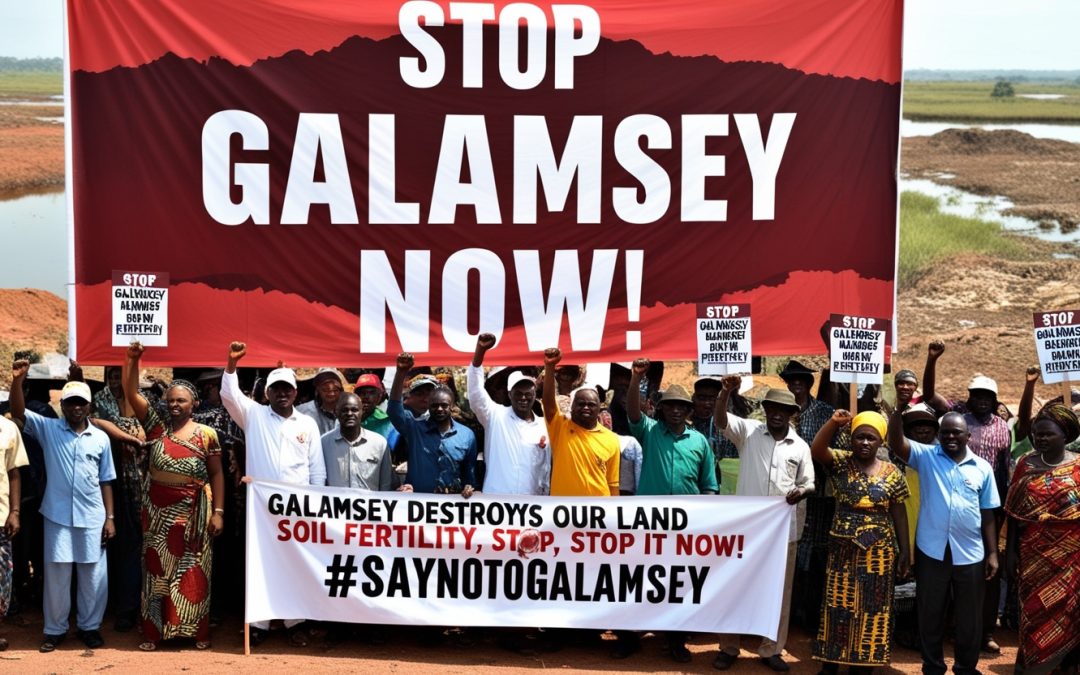

Let us speak honestly. When people in Accra and the big cities condemn galamsey, it is not because they have suddenly become lovers and defenders of the environment. It is because polluted water systems and ecological collapse now threaten their comfort.

If these same voices cared genuinely about justice for the land and people, they would have used their social and political capital long ago to fight for rural development. They would have demanded viable economic systems for every Ghanaian, not a handful of city dwellers. They would have pressured leaders to decentralise opportunity.

Instead, they remained silent, until the crisis touched them.

So we must ask: is it environmental love or urban self-preservation that drives their anger?

Because if it was truly love for the environment and for the country, they would fight with equal passion for economic justice for the people who feed the cities. They would demand alternatives for rural youth. They would call for investment in agriculture, processing, rural industry, and rural infrastructure with the same energy they tweet about river pollution.

Ask any of them to identify a serious economic policy the government has implemented to uplift rural Ghana, and listen to the silence. As a result, we have created a phenomenon where when you travel from the city to the village, we are made to feel big like big boys and big mamas, when everyone in the village comes asking you for bread, biscuits, soap, yam phone etc you brought to them. Do any of us get worried that those petty things, are the things they crave to get in the village? We may have thought that this is where they belong, not so?

That’s because, for generations, the Ghanaian state failed to build an economy that could carry everyone along. Development was not a bridge; it was a filter. Those who could migrate to the cities found opportunity; those who could not were left behind to watch their futures fade into the dust of abandoned farms and collapsing rural towns. The message from the state was clear: prosperity lives in Accra and Kumasi; the rest of you must learn to survive.

That’s because, for generations, the Ghanaian state failed to build an economy that could carry everyone along. Development was not a bridge; it was a filter. Those who could migrate to the cities found opportunity; those who could not were left behind to watch their futures fade into the dust of abandoned farms and collapsing rural towns. The message from the state was clear: prosperity lives in Accra and Kumasi; the rest of you must learn to survive.

Those who stayed back in the villages were not lazy. They were trapped. They either had no relatives in the city to house them, or those had no savings to fund their relocation. Others had no networks to open doors. They remained in rural communities where schools had no resources, clinics had no doctors, roads had no maintenance, and the soil; once a lifeline, slowly gave up under the weight of exploitative middle men who bought their produce cheaply, and neglect. Development never arrived. Hope quietly packed its bags and moved to the city.

Then galamsey came, and for many, it was not a crime; it was salvation.

Suddenly, young men who once begged for transport fare could buy motorbikes. People no longer ask for yam phones, bread or biscuits, but they own even better versions of these. Women who once chased customers to buy gari could feed their families confidently. Parents who once prayed over sick children because hospitals were far and expensive now had money for treatment. In a nation where economic mobility is reserved for the urban lucky, galamsey felt like the first real redistribution of opportunity.

Now the same government and the elite that abandoned these communities wants to arrest them for choosing survival. The same political class that has benefitted from this trade now arrives with soldiers, excavators, and moral lectures, insisting that they care about the land and the rivers. To many communities, this is not environmental governance, it is punishment for daring to succeed without permission.

Then there is the open, state sponsored price gimmicks, and political chess of cocoa farmers.

Cocoa Farmers: The Original Betrayed Majority

Before galamsey, Ghana had another group of rural heroes: cocoa farmers. For decades, they fed the economy. But who among them drives the cars city workers buy? Who among them sends their children abroad the way managers and middlemen in Accra do? Who among them earns even a dignified living?

The cocoa farmer breaks their back for beans; the system reserves wealth for those who supervise from boardrooms. Managers prosper. Exporters prosper. Politicians prosper. The farmer? Survival. Where are the elites?

Your silence and no practical interventions have fueled exploitation masquerading as national pride. So when cocoa farmers, tired of low prices, tired of disrespect, tired of a system that feeds everyone but them, decide to sell their land to galamsey operators, who exactly is to blame? Before we condemn them, ask: what did the state offer them instead?

If the middle class and the government do not want cocoa lands destroyed, let them first destroy the injustice in cocoa pricing and power. Let the farmer be wealthier than the bureaucrat who “oversees” their toil. Let rural labour be rewarded more than urban paperwork.

Until then, galamsey will continue to look like the balance, because for once, the villager tastes dignity.

Which is why I say that Galamsey is not a rebellion against the environment. It is a rebellion against abandonment. It is a reminder that people will always choose survival when the system gives them nothing else. Right now your dose to cure our century old problem is to destroy the excavators, arrest the boys, and flood communities with soldiers. However, until you build a fair economy, the soil will always be an exit door for the desperate. Any nation that refuses to build justice should not act surprised when the poor build their own, even if it comes in the form of mud, mercury, and gold.

For the elite and the government, if we want to stop galamsey,

- Do not fight the symptom. Fight the root.

- Do not criminalize rural survival. Fix the economic betrayal that made galamsey attractive.

- Do not police miners, create systems where farming, forestry, and rural labour make a person proud to stay home and succeed.

Only then will the land, and the people finally breathe.