Between 2009 and December 2016, Ghana started its modern battle against illegal small-scale mining. It was the leadership of Late John Mills, and later President John Dramani Mahama who led the fight within this period. The Galamsey taskforce established by President Mahama had people such as Alhaji Inusah Fuseini, the then Minister for Lands and Natural Resources, who was the Chairman; Mr Mark Woyongo, Minister for Defence, and others led to high-profile arrests, mass deportations of foreign nationals, and repeated attempts to stop the widespread destruction of rivers, forests and farmlands. Yet, despite the strength of the response, galamsey continued to flourish, revealing deep structural weaknesses in enforcement and governance.

This article traces the major actions, numbers, institutions, successes and failures that defined the fight against galamsey over these eight years.

2009-2012: Rising Pressures and Fragmented Enforcement

In the early years of the period, galamsey expanded rapidly across the Western, Ashanti, Eastern and Central Regions. River pollution, farmland destruction and safety incidents increased sharply. Enforcement, however, remained largely fragmented.

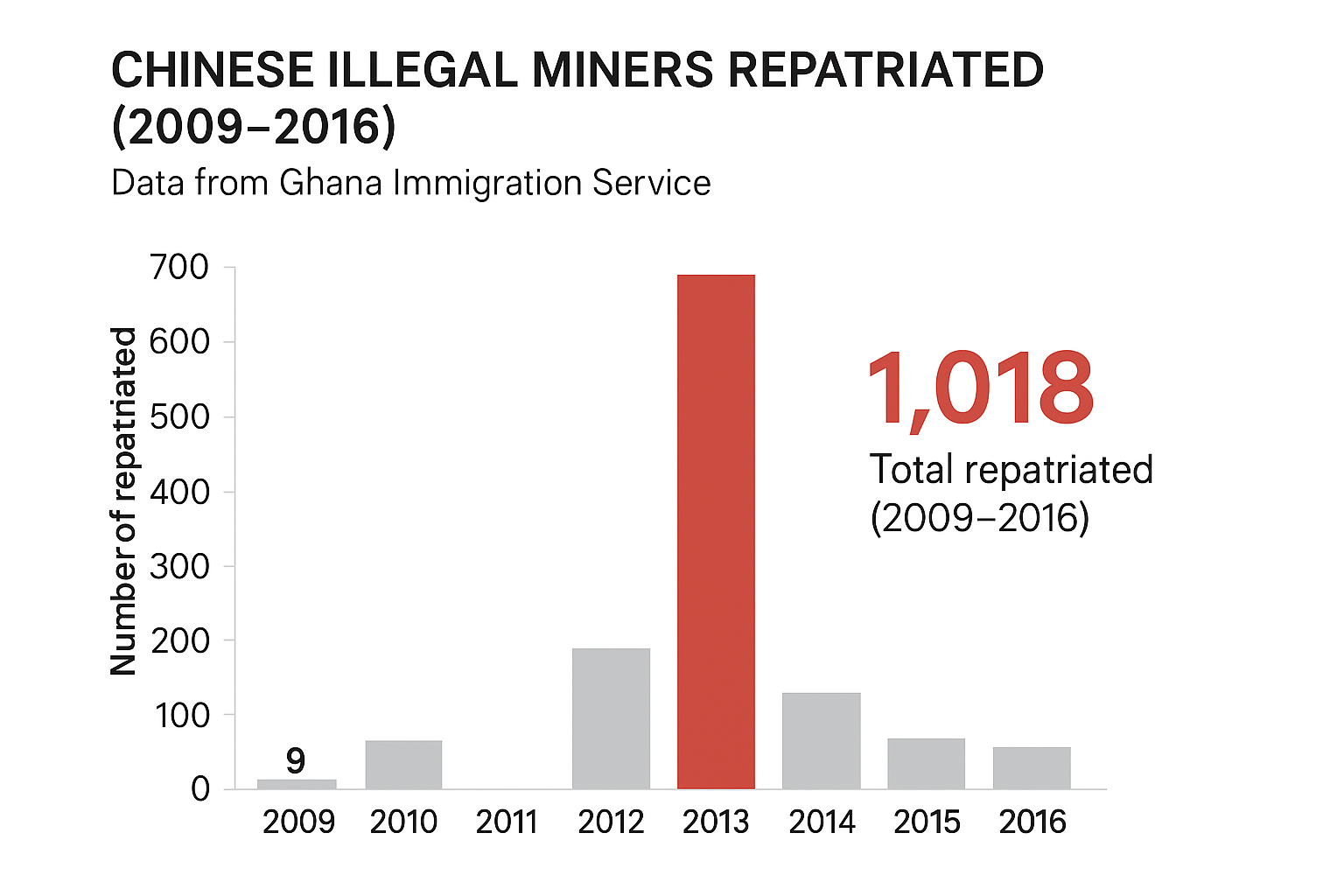

Police and district assemblies carried out sporadic raids. Some foreigners involved in illegal mining, particularly Chinese nationals who were starting to introduce excavators into small scale mining were arrested and repatriated, though in small numbers. Ghana Immigration Service data later compiled from this era recorded repatriations such as 9 in 2009 and 43 in 2010, but no sustained national strategy existed. There were no reparations in 2011.

By 2012, the environmental damage and the growing involvement of well-organised foreign groups had turned galamsey from a local problem into a national crisis, setting the stage for more drastic action.

2013: The Year of the Big Crackdown

Public anger peaked in 2013 as rivers turned brown, forests disappeared and entire communities complained about the takeover of farmlands by illegal miners. Media investigations at the time highlighted foreign-led operations, especially those using heavy machinery. In response, the government established the Inter-Ministerial Task Force on Illegal Small-Scale Mining, a security-led initiative that coordinated the police, immigration, military and key ministries. This became the central enforcement body until 2016.Mid-2013 saw the most dramatic actions. Police and immigration officers arrested more than 160 Chinese miners in June alone, and dozens more in the months that followed. International media captured images of seized machines, dismantled sites and busloads of arrested foreigners.

Later compilations by the Ghana Immigration Service reported a staggering 713 Chinese nationals repatriated in 2013; the single highest annual figure on record during the 2009-2016 period. This spike represented the height of Ghana’s direct, forceful confrontation with foreign-led galamsey.

Chinese illegal miners repatriated 2009-2016

Visible Impact, but Temporary

For a time, the crackdown appeared effective. Some hotspot districts saw a sharp drop in illegal mining, and the presence of soldiers and immigration officers created a sense of urgency. Heavy machinery, including excavators and “chang-fa” dredging machines was seized or destroyed.

But the campaign’s weaknesses soon became clear. Many arrested miners were repatriated rather than prosecuted, and the networks that financed and supplied the activities remained largely untouched.

2014-2016: Continued Raids, Fewer Deportations, Persistent Problem

After the 2013 “flush-out,” enforcement continued but with reduced intensity. Localized raids occurred across multiple regions, and Immigration Service figures show lower; but still significant, repatriations: 74 in 2014, 21 in 2015 and 28 in 2016.

Government agencies, including the Minerals Commission, Forestry Commission, district assemblies and the police, attempted to regulate the sector through licensing drives and renewed local enforcement. But the underlying challenges remained unsolved:

- Many operations simply moved to new locations after raids.

- The financiers and equipment suppliers behind the industry rarely faced prosecution.

- Illegal mining proliferated along major rivers such as the Pra and Ankobra, worsening turbidity and damaging aquatic ecosystems.

- Communities dependent on mining had no strong alternative livelihood programmes, driving locals back to galamsey once security forces withdrew.

By 2016, it had become clear that the gains of 2013 were not sustained.

Anti Galamsey Efforts Evaluation Infographic

| What Worked | What Didn’t Work |

| Strong early deterrence in 2013: The coordinated military-police crackdown temporarily reduced illegal operations and sent a strong signal of state authority. |

Lack of sustained, long-term strategy: The response was operational rather than systemic. When the military withdrew, galamsey quickly re-emerged. |

| Disruption of some foreign-led operations: Large-scale repatriations, especially in 2013, reduced the visibility and dominance of foreign miners in certain districts. |

Weak prosecution and justice gaps: Most arrested individuals—particularly foreigners—were deported rather than prosecuted, reducing deterrence. |

| Increased national attention: The crackdown brought unprecedented public awareness, academic research, media coverage and diplomatic engagement on the galamsey issue. |

Failure to target the real power brokers: Financiers, equipment suppliers, corrupt officials and political intermediaries were rarely confronted. |

| No large-scale reclamation or livelihood support: Environmental restoration and alternative income projects lagged far behind enforcement efforts. |

|

| Fragmented institutional coordination: Multiple agencies acted independently, leading to overlap, inconsistent enforcement and weak accountability. |

Conclusion: A Fight Begun but Not Finished

The 2009–2016 period represents Ghana’s first major attempt to confront galamsey with decisive national force. The 2013 crackdown, in particular, remains one of the most dramatic anti-galamsey operations in the country’s history, marked by unprecedented arrests, deportations and equipment seizures.

Yet the persistence of illegal mining shows that enforcement alone was not enough. Galamsey proved more organised, more economically embedded, and more politically complex than short-term taskforces could dismantle. The years after 2016 would demonstrate that without deep structural reforms—targeting financiers, regulating supply chains, strengthening institutions, and providing real economic alternatives—the fight against galamsey cannot be won through raids and deportations alone.

This period laid the foundation for later strategies, but also revealed the critical gaps that future governments would struggle to close.